VIENNALE 2015 (02): THE MAN FROM ITUZAINGÓ: THE CINEMA OF RAÚL PERRONE

Roger Koza

In early April, I paid a visit at Raul Perrone’s home. I’d already avoided some of his invitations before and I had two reasons to do so; the time-consuming journey from Buenos Aires to Ituzaingó—though the actual distance is not that long, it’s only 22 miles away—and keeping a respectful distance from filmmakers I admire out of shyness but also prudence, since it is not always advisable to get to know personally those one believes to be true masters. But this time I had to accept the invitation—the Viennale tribute was confirmed and Perrone wanted to show me three virtually-finished new films which could take part in the program.

The procession to Perrone’s home in Ituzaingó by critics and program producers has almost become a classic sight for Argentinean film buffs. It is usual to see BAFICI’s (The Buenos Aires International Festival of Independent Film) directors and program producers, as well as some first-order critics on their pilgrimage to Perrone’s house in order to watch his new films. This is a director who is neither fastidious nor easy-going and truth is there are several reasons why Perrone usually does not leave his house (or his beloved Ituzaingó, where he undoubtedly is some sort of local hero); he is known as a phobic character that doesn’t travel abroad and even avoids a journey to Buenos Aires, and if one of his films opens at BAFICI he only attends the premiere for the Q&A session, the press conference, and that’s it—off he goes, straight back home. This hurrying to return home is a key element in an artistic and obsessive behavior which, in his case, does define a lifestyle—for him, cinema is a trade (and a challenging call) which demands absorption and work. Distractions are the enemy for filmmakers.

Perrone is a self-taught director. He never went to a film school and never worked as the assistant of some well-known master. His relation with images was formed during his draftsman days, when he was working as such for two well-known Buenos Aires journals—Tiempo Argentino first and El Cronista Comercial later—from the late 1970s to 1985. For him, cinema began the decade when VHS became popular in Argentina and when cameras to record in that format became accessible. The evolution, and associated democratization, in the gadgets to register images have determined Perrone’s films. He is a filmmaker who never asked the Argentinean Instituto Nacional de Cinematografía (National Film Institute) for grants and never received any support from the international coproduction funds. Perrone’s independence is not a myth or a metaphoric attribute bestowed by us critics to define his films. For him, independence is not an evidence but a consciously chosen political stance as well as a sustained practice of his own preaching, showing a remarkable coherence which has also translated into an ever-evolving poetics which never remains the same but keeps, discreetly, an unifying shared idea that can be seen throughout all his films.

And, by the way, the story about people visiting Perrone’s house is far from merely a rhetoric device or an unnecessary autobiographic glimpse—home is a decisive factor in Perrone’s creative activity. Placed in a working-class neighborhood in Ituzaingó, his modest house has a garage in which he can be found working each and every day. That’s where he writes and edits his films; alone, in an obsolete computer which few would ever associate with the everyday working tool of an active filmmaker. The conditions in which Perrone produces his films are so austere it is even painful, and surprising, to watch. The place looks rather as a carpenter’s workshop, or as the atelier of an unknown painter, and not as a filmmaker’s—perhaps the most unique one in Argentina—secret enclave. Perrone’s Center of Operations represents the subconscious of his films. Outside from it, he has a whole Cinecittà of his own; all of Ituizangó is there for him to use for locations, he’s been filming there for over two decades and most of his actors and crew members—many of them friends and “alumni” who have “graduated” from the famous free workshops (organized by Ituzaingó’s municipality) where Perrone teaches his craft—come from that town.

II

Would it be enough to simply say Perrone’s films are essentially defined by the diversity of portraits of Ituzaingó he’s shot? Is he a local community biographer? He is that, indeed; in his films we find local children, adults, and senior citizens who are the protagonists of his kind stories. Is he a seismographer of his times? He is that, too; historic events which defined the frame of his community’s social reality were always present—in an indirect but also very precise way—in his movies: socioeconomic degradation during the Menem years in the 1990s can be seen through its effects in films such as Labios de churrasco, Graciadió, and La mecha; likewise, from 8 años después to P3nd3jo5, his more recent films manage to provoke distrust towards the so-called Argentinean economic miracle which happened in the middle of the 2000s. The so-called abundance of recent years in Argentina, isn’t it refuted by the existential downfall of the skaters shown in P3nd3jo5, as they glide down through a present time which is drifting away? And what can be said about the collective mood of the characters in Los actos cotidianos, a film which stands as a witness to the precariousness of all living orders?

However, Perrone is never constrained to the limits usually imposed to sociologic, or even denounce films. He’s got different interests, related to those brief glimpses of beauty that happen during the flow of a time marked by repetition and no prospects for the future. This entails a behavior, a gesture, a form. Sooner or later, Perrone’s characters raise their eyes upward, towards the sky, as if that direction offered a poetical vanishing point. This attitude could involve a theological gesture but it doesn’t, though in his films Christian icons are constant and religion has a place as an honest response in terms of registering the symbolic possession of a people. Rather, this vertical vanishing point is an operation of the imagination, a poetic elevation making reference to a different sensitivity, opposed to worldlier, denser matters. That’s why images of the sky are so important in all of his films; the sporadic announcement through the sound of rain in La mecha, the beautiful super-imposed shots of the sky and trees in Samuray-S, or the playful levitation of the three characters at the end of Graciadió. In Perrone’s films the sky is an axis of sensitivity, a visual force which inspires and enables a different way to organize the perception of things and people’s lives.

III

Until now, there are two distinct stages in which Perrone’s work can be divided; first, a long period that began with his earliest movies—shot in video and other digital formats in the late 1980s—and ended with Las pibas, only four years ago; and, then, the radical poetic turn he experienced in P3nd3jo5, the film which opened the second stage, or movement, of his work. For over two decades, Perrone’s work could be defined as some sort of (poetic) realism dominated by the spoken word, and it was evident he favored the use of frequent static medium shots and discreet extra-diegetic music, keeping formal experimentations only for occasional, well-defined moments.

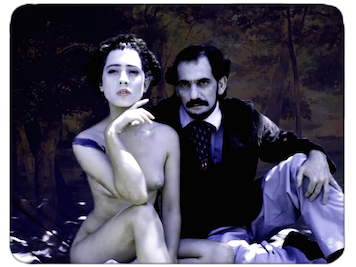

P3nd3jo5, on the other hand, opened an unpredictable change of paradigm in which a very personal form of materialistic expressionism became Perrone’s dominating poetics. He began to perceive the visual juxtaposition between painting and cinema and the fact digital evolution of the image was forcing him to rediscover the material (and virtual) texture of images; however, paradoxically, that very same drive would also send him directly back to the beginnings of cinema. In the digital era, it is necessary to revisit and dialectically examine the prehistoric grammar of cinema’s language, that’s a new synthesis that has to be achieved. In a way, at first this shifting back towards the past was limited only to the image, but the sound concept that began in P3nd3jo5 is directly derived from pop music. In Perrone’s most recent films there is always an aural background that reminds us of the sound of a DJ’s needle, as if the whole sound structure of his films were organized by a principle of musical intervention, used as the guiding concept even for the visual treatment in Samuray-S and also in Hierba; Perrone intervenes filmic shots in the former, and paintings made by different artists in the latter. He appropriates these works to use them in a completely different symbolic universe within an enormously vast system of representation.

This new period—more avant-garde if you will—has left Ituzaingó slightly out of frame as the symbolic space for Perrone’s tales; however, curiously, this hasn’t meant severing his connection with some sort of sensitivity for popular culture. His interest for the fables and folk tales from the past opens a new path for this filmmaker’s restlessness.

At 63, the true father of Argentinean independent cinema is going on at full force. Perrone keeps in his search, exorcising—through unbelievable aesthetic feats—that outdated decree which foresaw cinema as an invention with no future.

This text was originally commissioned by Viennale.

English version Tiosha Bojorguez.

Roger Koza / Copyleft 2015

Últimos Comentarios